1930-1939

1930

Isabetta in Cuba with Carlos’s family, Adolfina, Tio and Adoris c.1930

May 1: Enríquez leaves for Cuba with Isabetta. He plans to leave Isabetta with his family and travel with Neel to Paris. Neel sublets her apartment in New York and goes to her parents’ house in Colwyn. She travels every day to Philadelphia to work at the Washington Square studio of art school friends, Ethel Ashton and Rhoda Meyers.

July: Enríquez, with not enough money for two to travel, goes on to Paris without Neel. Neel spends a summer of exhaustingly intense painting.

August 15: Neel returns to Colwyn after painting at Meyers and Ashton’s studio and suffers a nervous breakdown. She recalls experiencing a ‘chill that lasted at least eight hours’ (Hills, Alice Neel, p. 32). She is cared for at home by her mother. In an undated handwritten text (Neel Archives) she writes: ‘Carlos went away. The nights were horrible at first ... I dreamed Isabetta died and we buried her right beside Santillana.’

Alice Neel- Suicidal Ward, Philadelphia General Hospital, 1931, pencil on paper, 17 x 22 in.

October: Neel is hospitalized at Orthopedic Hospital in Philadelphia.

1931

January: Enríquez returns to the United States. He visits Neel a few times in the hospital and takes her home to her family in Colwyn. Shortly after Neel is back home, she attempts suicide by turning on the gas oven in her parents’ kitchen. She is hospitalized at Wilmington Hospital in Delaware. After a few days she is returned to Orthopedic Hospital in Philadelphia, where she smashes a glass with the intention of swallowing the shards; attendants are able to prevent her from harming herself. She is sent to the suicidal ward at Philadelphia General Hospital the following day until after Easter. Enríquez returns to Paris.

Late Spring: Neel is transfer to the suicidal ward of Gladwyne Colony, a private sanatorium in Gladwyne, Philadelphia, directed by Dr. Seymour DeWitt Ludlum of the Neuropsychiatric Department at Philadelphia General Hospital. She is encouraged to continue drawing and painting, in contrast with current conventional treatment which stopped all professional life activities.

1931

Summer: Enríquez travels from Paris to Spain. In letters to Neel at Gladwyne Colony he expresses concern for her and says that Fanya Foss sent news of her.

September: Neel is discharged from Ludlum’s sanatorium and returns to Colwyn. She visits Nadya Olyanova and her Norwegian husband, Egil Hoye, a sailor in the merchant marine in Stockton, New Jersey. There she meets Kenneth Doolittle, also an able-bodied seaman and a close friend of the couple.

1932

Early in the year, moves with Kenneth Doolittle to 33(?) Cornelia Street in Greenwich Village.

May 28-June 5: Participates in the First Washington Square Outdoor Art Exhibit, showing several paintings. She is forced to withdraw Degenerate Madonna following Catholic Church protests. There she meets John Rothschild (1900-1975), a Harvard graduate from a wealthy family who runs a travel business. Their friendship will last throughout their lives.

June 5: The New York Times Magazine, in an article titled ‘Open-Air Art Shows Gaining Favor’, reports:

New York has just had its first open-air art show, staged in Washington Square by the artists of Greenwich Village. New to us, these outdoor exhibits are familiar sights in several European cities, and in Philadelphia. Hard times have hit the artists of the Village; the outdoor sale was held to help them market their wares and perhaps to gain recognition for their talents.

November 12-20: Participates in the Second Washington Square Outdoor Art Exhibit, which includes the work of about three hundred artists. Juliana Force, who endorsed the exhibits, calls a meeting on November 20 with the artists: ‘Mrs. Juliana Force, Director of The Whitney Museum of American Art, invites you to tea at The Jumble Shop, 11 Waverly Place, on Sunday, ... for a round table discussion concerning the problems of the winter’ (Washington Square Outdoor Exhibition records, 1932-1957, Archives of American Art).

1933

Painting c.1933 by Alice Neel of the kind submitted to the WPA

January: Participates with Joseph Solman in an exhibition at the International Book and Art Shop on West Eighth Street. Solman will be a founding member of the abstract art group The Ten and will include Neel in a number of group shows over the years.

March 16-April 4: Exhibits in Living Art: American, French, German, Italian, Mexican, and Russian Artists at the Mellon Galleries in Philadelphia, organized by J. B. Neumann. Two of her paintings are mentioned in the review in the Philadelphia Inquirer (March 19): ‘Among the Americans there is a one-time Philadelphian, Alice Neel, whose “Red Houses” and “Snow” reveal the possession of interpretive gifts out of the ordinary. There is nothing “pretty” about these pictures, but they have substance and honesty.’

March and October: Participates in two exhibitions and art sales for needy New York artists organized by the Artists’ Aid Committee, which is headed by Vernon C. Porter, chairman of the Washington Square Outdoor Art Exhibits.

December 26: Enrolls in the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), a government-funded program run under the auspices of the Whitney Museum of American Art and its director Juliana Force, aided by Vernon C. Porter. She later recalls (New York City WPA Art: Then and Now, New York: NYC WPA Artists, 1977, p. 66):

“The first I heard of the W.P.A. was when in 1933 I received a letter from the Whitney Museum asking me to come and see them. I was interviewed by a young man who asked me ‘How would you like to paint for $30 a week?’ This was fabulous as most of the artists had nothing in those days and in fact there were free lunches for artists in the Village ... All the artists were on the project. If there had been no such cultural projects there might well have been a revolution.”

Paints Joe Gould, a well-known Greenwich Village bohemian who claims to be writing ‘An Oral History of Our Time’.

1934

Isabetta on boardwalk in New Jersey 1934

January: Enríquez returns to Cuba from Spain following the death of his mother. He writes to Neel expressing a desire to get back together. She, however, is entangled with Kenneth Doolittle, and being pursued by John Rothschild. It is too much for her. Although she and Carlos never obtain a divorce or annulment, they never meet again.

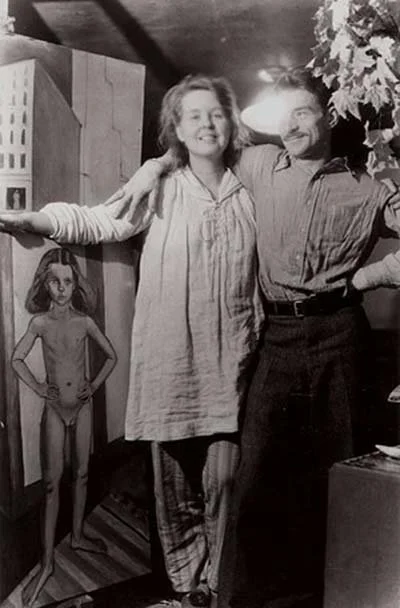

Neel and Doolittle with the painting of Isabetta 1934

April 17: Neel is separated from the PWAP payroll. According to an internal memo, on February 12 she had delivered a painting ‘of good artistic merit but so inappropriate that it was considered useless.’ She was given a new assignment to paint a picture showing ‘one of the phases of New York City life.’ On April 15 she was asked to bring the picture to the office and appeared the following day without it, saying her original painting had turned out so badly that she had scraped it off the canvas and had begun again.

She delivered this painting on April 17, and ‘the opinion of those who viewed it was that it had been painted the night before on a brand new canvas and that it did not represent more than one day’s work, although she claimed to have been working on this picture two months.’

Summer: Rents a house with her mother on the New Jersey shore, in Belmar, New Jersey. Her mother and father come to spend the summer with her. Isabetta, now almost six years old, comes from Cuba to visit her.

It is here that she paints a nude portrait of Isabetta.

September 30: Neel is entered on the payroll of the Works Progress Administration (WPA; later the Work Projects Administration), which replaced PWAP, at $103.40 per month, in its easel division.

1934

December: Kenneth Doolittle, in a rage, burns more than three hundred of Neel’s drawings and watercolors and slashes more than fifty oil paintings. Neel’s painting of Isabetta is slashed beyond repair but later repainted.

Neel moves out and stays with John Rothschild, first at a hotel on West 42nd Street and then at 14 East 60th Street. With help from Rothschild and her parents, Neel buys a modest cottage in Spring Lake, New Jersey, at 506 Monmouth Avenue. Although she will later sell this house and buy a larger one, Spring Lake will be where she spends part of each summer for the rest of her life.

Rothschild has decided to leave his wife and children, the subject of a number of Neel’s paintings. He wants to live with Neel, but she is ambivalent about it. She gets an apartment for herself at 347 1/2 West 17th Street.

About this time, she meets Jose Santiago Negron, a nightclub singer. Negron leaves his wife and infant child, Sheila, and moves in with Neel. Sheila is the subject of at least three paintings.

Neel’s parents in front of the cottage in Spring Lake, N.J. c.1934

Jose Santiago Negron far left with his Salsa Band c.1935

1936

January 28: Receives notice of a WPA pay adjustment (to $95.44 per month).

Negron with Neel’s parents and his daughter Sheila at Spring Lake, N.J. railroad station 1939

June: Art Front, the journal of the Artists’ Union, an informal group of young radical artists who demand government patronage for the arts, publishes an illustration of Neel’s painting Poverty, 1930, now known as Futility of Effort.

September: Exhibits at the A.C.A. Gallery, New York, in a show of the winners of honorable mention in a contest held by the American Artists’ Congress. This organization was founded in 1935 by a group of artists that included Stuart Davis, Louis Lozowick, and Moses Soyer. According to Davis’s introduction in First American Artists’ Congress (New York, 1936), their aim was to ‘achieve unity of action among artists of recognized standing in their profession on all issues which concern their economic and cultural security and freedom, and to fight War, Fascism and Reaction, destroyers of art and culture.’

Neel’s painting, Nazis Murder Jews, is singled out in a review by Emily Genauer in the New York World Telegram (September 12):

Alice Neel brandishes aloft the torch which she and the members of the Artists Union along with her hope will eventually lead to enlightenment and the destruction of Fascism. One, depicting a workers’ parade, would be an excellent picture from the point of view of color, design and emotional significance if the big bold black-and-white sign carried by one of the marchers at the head of the parade, didn’t throw the rest of the composition completely out of gear by serving to tear a visual hole in the canvas.

1937

July: Neel is hospitalized for a miscarriage in her sixth month of pregnancy. Her mother writes to her at Gotham Hospital in New York (July 12, Neel Archives): ‘You poor child suffering so, and no one with you ... you were sick longer than with Isabetta. I am so very sorry for you but for myself delighted, you don’t realize all you would have had to face.’

Nadya Olyanova (Mrs. Egil Hoye) also writes to Alice from Stormville, New York, asking her to visit and promising to take care of her (July 16, Neel Archives): ‘Could you get some word to me some way? Through John perhaps? Take care of yourself as your mother says, “Alice don’t get wreckless.”’ Sometime after her hospitalization, she moves with Negron to 129 MacDougal Street in the Village.

July 10: Receives notice of another WPA pay adjustment (to $91.10 per month).

1938

Moves to Spanish Harlem (East Harlem), 8 East 107th Street, with Negron.

May 2-21: Exhibits sixteen paintings in her first solo exhibitions in New York City, at Contemporary Arts, 38 West 57th Street. Howard Devree, a critic for the New York Times, writes (May 8):

Alice Neel in her debut at Contemporary Arts tempers her firm constructions with a somewhat sardonic humor in which a couple of remarkable cats play a part. Her “Classic Fronts” (red brick facades) and a still-life with torso and sprays of foliage are outstanding in the show. It is an excellent “first”.

Neel is included in at least three group shows at Contemporary Arts this year.

May 23-June 4: Shows four paintings in the exhibition The New York Group at the A.C.A. Gallery. Also in the show are Jules Halfant, Jacob Kainen, Herb Kruckman, Louis Nisonoff, Herman Rose, Max Schnitzler, and Joseph Vogel. The exhibition brochure declares:

The New York Group is interested in those aspects of contemporary life which reflect the deepest feelings of the people: their poverty, their surroundings, their desire for peace, their fight for life. However, we believe that this laudable attitude can best be transformed into living art by utilizing the living tradition of painting. There must be no talking down to the people; we number ourselves among them. Pictures must appeal as aesthetic images which are social judgements at the same time.

Isabetta standing with Negron’s guitar 1939

1939

February 5-18: Exhibits three paintings in the second exhibition of the New York Group at the A.C.A. Gallery. In the brochure, the poet Kenneth Fearing writes:

With its second showing, The New York Group gives lively emphasis to its original program ... These pictures ... are as savage, as primitive, as man is in today’s civilization, as sensitive, as the individual is against the contemporary background of sheer chaos. That, essentially, is the point that these pictures, esthetically sound and socially valuable, make through the separate and distinct personalities of this exhibit.

July 18: Receives notice of a WPA pay adjustment (to $90.00 per month).

Neel sitting with her mother in Spring Lake, holding Negron’s guitar, 1939

Summer: Isabetta travels from Havana to visit Neel who is in Spring Lake with her parents and Jose Negron.

Neel visits the World Fair in New York with John Rothschild.

August 17: Neel is terminated from the WPA.

September 14: Birth of Neel’s and Negron’s son, Neel, later called Richard.

October 24: Alice Neel is reassigned to the WPA.

December: Negron leaves Neel and his 3‑month‑old son. According to Neel he met a saleswoman at Lord and Taylor.

1939 - 40

Winter: Meets Sam Brody (1907-1985), a photographer and filmmaker who was one of the founding members of the Film and Photo League, a radical filmmaking cooperative. She and Brody begin a relationship. He is married and has two children, Julian and Mady, of whom Neel paints several portraits. (He will marry again later and will have one more son, David, whom Neel will also paint). They will live on and off together for the next two decades.

Isabetta in Spring Lake with Neel’s parents and Neel, pregnant with her third child, Richard 1939 (photo presumed taken by Negron)

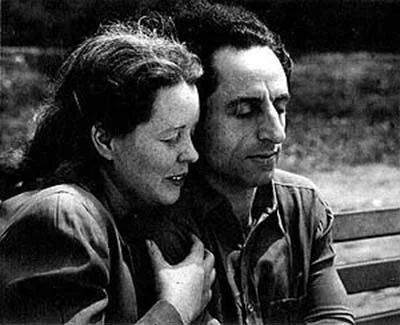

Neel and Sam Brody c.1940